Birmingham was built, literally and figuratively, by steel, iron and coal. This is no secret. The massive statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalworking, who keeps an eye on the city from atop Red Mountain is a dead giveaway. So, too, are the remains of plants like Sloss Furnaces — catacombs of an economy of yore.

Though the medical and financial sectors have overtaken iron and steel as the primary economic drivers of the region, heavy industry is still a major player. The plumes of smoke that today billow from smokestacks across Jefferson County are proof enough. Heavy industry (and the air pollution that comes with it) continues to play a significant role in our local economy and identity.

We have made great strides in improving air quality since the Clean Air Act of 1970 was signed into law. But research shows that even “safe” levels of air pollution are still harmful to our health, especially for vulnerable populations like pregnant women, children, seniors, and people living with lung and heart diseases. On top of that, studies have also found that air pollution tends to affect low-income and minority communities more than higher-income and white communities. When you add all of this up, it paints a stark picture: air pollution persists today, and it affects those who need protection most of all.

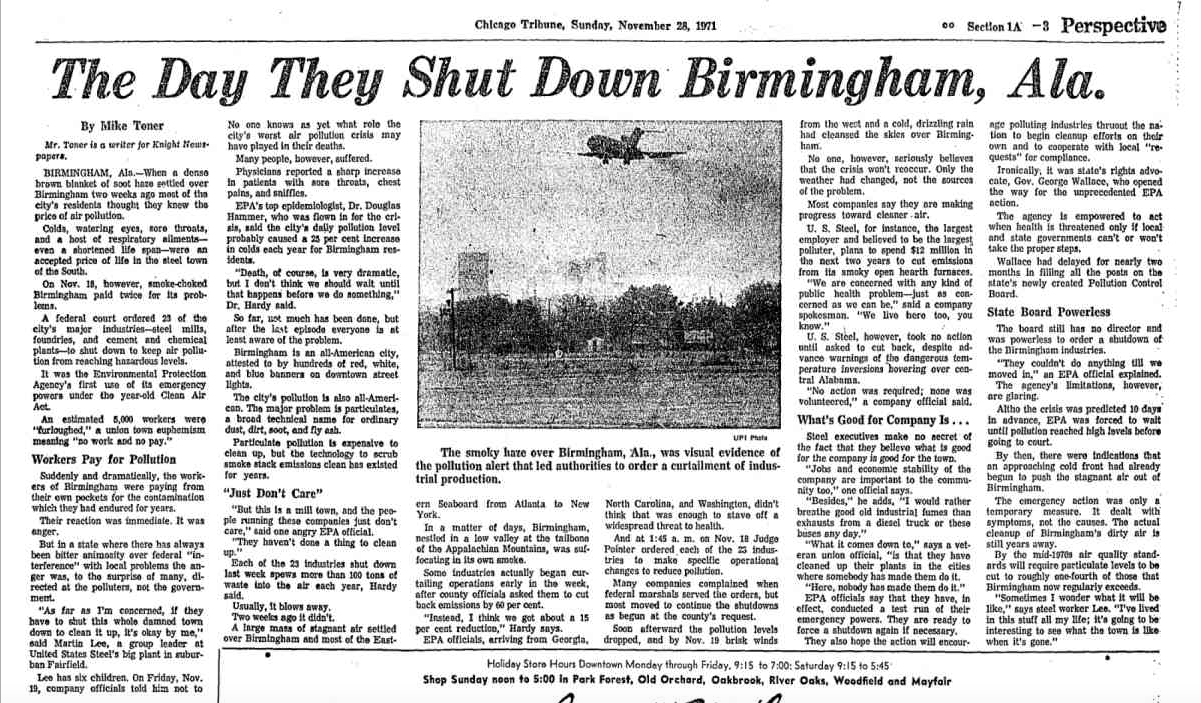

Let’s back up and remember how progress was made. Forty-four years ago Birmingham was in the throes of a public health crisis. Unseasonably warm temperatures and a high pressure system created a perfect storm, trapping air pollution pouring from steel and coke plants. Pollution reached dangerous levels.

Local health officials, elected officials, and industry struggled to figure out what to do. Industry was asked to voluntarily reduce emissions; the smaller facilities agreed, but the five largest contributors to the pollution refused to compromise. This was uncharted territory, but something had to be done to abate the pollution covering the city like a black cloud.

It’s important to remember the historical context of these events. The Clean Air Act gave the EPA the authority to enforce air regulations and to compel states to do the same. Alabama did create an Air Pollution Control Commission in early 1971, but Governor George Wallace didn’t seem to be in any hurry to appoint members to the board — thus delaying state enforcement of the Clean Air Act.

And so the newly formed EPA came to town to exercise its authority under the Clean Air Act. Eventually, U.S. District Court Judge Sam C. Pointer, Jr., granted the EPA a restraining order halting industry operations — an unprecedented move. Plants shut down for a day, the weather system finally dissipated, and pollution levels subsided. Today, November 18 is known as “the day they shut Birmingham down.”

GASP plans to pay tribute to the progress we’ve made since that week forty-four years ago at an event at Ruffner Mountain Nature Preserve Wednesday, Nov. 18 from 5:30–8:30 p.m. But more importantly, we will look ahead to how we can win a healthier future with cleaner air, renewable energy, and transparency in all government and agency decisionmaking.

I invite you to come enjoy complimentary wine, beer, hors d’oeuvres and learn what our movement is all about. The event is free, but donations are welcome. A Toast to Clean Air is more than a social event, though. Our hope is that you’ll come away with a sense of urgency to support our mission for clean air and healthy communities.

In this season of Thanksgiving we have much to be grateful for, but there is still much work left to be done. And we can only do it if we work together. Will you answer the call?