A study published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health shows that even slight exposure to particulate air pollution may increase the risk of intrauterine inflammation (IUI).

Intrauterine inflammation (IUI) is one of the leading causes of pre-term birth, which can lead to lifelong developmental problems. For instance, research has found an association between pre-term birth and both autism and asthma. IUI occurs in one-in-nine births in the United States. The rate is higher for African-American women, where it occurs in about one-in-six births.

In other words, even small amounts of air pollution can harm not only pregnant women, but also the long-term health of their babies.

Another recent study tabulated that “the annual economic cost of the nearly 16,000 premature births linked to air pollution in the United States has reached $4.33 billion.”

Researchers analyzed data from 5,059 mother-infant pairs of the Boston Birth Cohort, a predominantly urban, low-income minority population. The team calculated the presence of IUI based on intrapartum fever (fever during labor) and placenta pathology (examining the placenta, which was collected and preserved after birth, under a microscope).

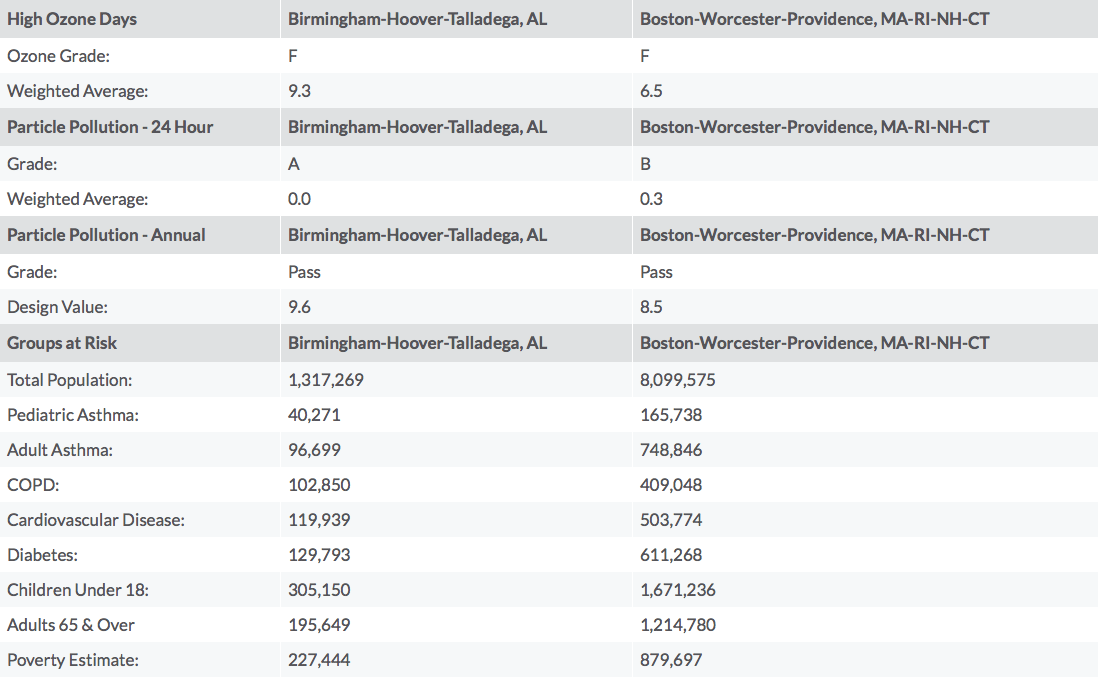

They used data from EPA air quality stations located near the mothers’ homes to determine maternal exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5), one of six criteria air pollutants regulated under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). Boston, where the women lived, had a similar score on this year’s State of the Air report from the American Lung Association. Birmingham ranked 22nd in year-round particle pollution, while Boston didn’t crack the top 25.

A comparison of Birmingham and Boston via stateoftheair.org. (Click to enlarge)

What did they find? The research showed the women exposed to the highest levels of air pollution were nearly twice as likely as those exposed to the lowest levels to have IUI. They also found that the first trimester may be the highest-risk period. And yes, before you ask, the researchers did control for factors like smoking, age, obesity … even education level.

So more exposure is associated with more risk. That makes sense. But, here’s a key point: most of the women’s air pollution exposure was actually below the EPA’s standard for fine particle matter. Less than a third of the women, 31 percent, were exposed to levels at or above EPA’s standard.

Senior author of the study Dr. Xiaobin Wang says, “Twenty years ago, we showed that high levels of air pollution led to poor pregnancy outcomes, including premature births. Now we are showing that even small amounts of air pollution appear to have biological effects at the cellular level in pregnant women.”

This Mother’s Day, I hope you will join in the fight for clean air. Science shows us quite plainly that there is no safe level of exposure to air pollution — and that is especially true for expectant mothers and their babies.

May is also Clean Air Month. Let’s say together with one voice that every mother and child deserves healthy air to breathe.