In early 2019, I joined with about 15 other climate activists in a series of meetings to study nonviolent direct action and movement theories of change with the goal of building a new approach to climate change at the scale of the crisis. Our work culminated in a January retreat in Washington, DC, where we finalized plans to launch this campaign in May. The retreat was the week after the first reported case of coronavirus in the United States. Little did we know that that virus would upend life as we knew it six weeks later.

The outcome of that project, I should mention, is a movement called Arm in Arm. The goal of Arm in Arm is to ignite a transformational era to end the climate crisis by centering racial and economic justice. Through months of rigorous research and debate, we developed a concept we call “disruptive humanitarianism,” which is this idea that we can do civil disobedience in a way that both highlights the injustices and absurdity of the status quo while also helping communities. We are using disruptive humanitarianism to build autonomous hubs throughout the United States with the hopes of mobilizing millions of Americans to engage in sustained nonviolent direct action.

The Arm in Arm frontloading team met throughout 2019 to study nonviolent movements and develop a model at the scale of the climate crisis

But, as I mentioned, coronavirus had other plans. The world as we knew it changed when, just six weeks later, the coronavirus brought our economy to a standstill. Conflicting reports about the coronavirus and the illness it caused (Covid-19) led to a whole lot of confusion. Months into this pandemic we still don’t know everything we need to know about the coronavirus, but we knew even less then.

If you’re anything like me, you remember those first few weeks vividly. Growing up in Memphis, I loved playing and watching basketball. So I suppose that’s why the first time I remember thinking, “oh wow, this is bad,” was when the NBA shut down mid-game on live TV. Schools, offices, and retail stores followed suit.

There was a real sense of confusion, which resulted in panic-buying and hoarding. (Remember when, for some reason, toilet paper was nowhere to be found?) Disinfectants, hand sanitizer, alcohol, and other items sold out in stores and online immediately. Grocery store shelves were wiped out.

Then the layoffs started — massive, unprecedented layoffs of millions of American workers.

As the world ground to a screeching halt and families began to shelter in place, systemic inequalities shone through more pronounced than ever. The people most vulnerable to Covid-19 — seniors, poor people, people of color, and people with underlying health conditions — struggled to get the personal protective equipment (PPE) they needed to keep themselves and their families safe.

Everyday people couldn’t get tested when they needed to, and when they did get tested the results often took days and even weeks to get back. Meanwhile, politicians and wealthy elites were able to get a PPE, rapid tests and health care pretty much on demand.

It was maddening.

The U.S. Congress eventually passed some relief bills aimed at aiding unemployed people, vulnerable groups, and struggling families and businesses. (Unfortunately, they also gave huge bailouts to mega corporations that didn’t need them — at least not as badly as we, the people. But that’s a topic for another day.)

It was in these early months that I texted my friend Keisha Brown who lives in Harriman Park in North Birmingham. We were checking in with each other and Keisha mentioned that folks in the community didn’t have what they needed … things like masks, disinfectants, hand sanitizer, soap, and healthy food. But before I get to that, I need to provide some context.

The view from Erwin Dairy Road looking south towards Collegeville, Fairmont and Harriman Park. Downtown Birmingham, in the background, is only a couple miles away.

Harriman Park is part of the 35th Avenue Superfund Site in North Birmingham. The EPA has been digging up contaminated soil in the community for the past six years, while several factories still pollute the air day-in and day-out. Keisha’s home is just a few yards away from Bluestone Coke, a cement plant, a concrete plant, an asphalt plant, a quarry, and other polluting facilities. The 35th Avenue Site also happens to have been caught up in a massive political corruption scandal involving a coal company, a law firm, and a former lawmaker.

Many of Keisha’s neighbors are very old and/or very sick, due in part to lifelong exposure to toxic pollution. In other words, places like Harriman Park are extremely susceptible to pandemics like this one.

We have been working with the North Birmingham community for about a decade trying to reduce the air pollution while helping to organize the community for what they want and need. Last year, our Climate & Environmental Justice Organizer Nina Morgan helped to develop a new program that we call the “Community Listening Sessions,” which is essentially just a community meeting to talk about hopes and dreams for the neighborhoods and how to get there. We serve food and fellowship. We laugh. We’re really honest with each other. (As Keisha says, “we keep it real.”) It really is all about listening, hence the name!

Our Community Listening Sessions are an opportunity to folks living in the 35th Avenue Superfund Site and their allies to put together a vision for a healthy, vibrant North Birmingham.

During these meetings, residents told us about their desires for a vibrant community with clean air, thriving small businesses, green spaces, and access to fresh food (among many things). When the coronavirus shut down our economy and threatened the health and well-being of the North Birmingham community, Keisha was quick to remind me that she and her neighbors had already told us what they want and need. Those needs had only become more urgent.

Luckily, we were able to bulk order some face masks and hand sanitizer online. We started collecting fresh produce (thanks to the federal Farmers to Families USDA program) as well as other grocery store items and necessities. Keisha got on the phone and called some neighbors and put together a distribution list. And we started delivering groceries, masks, and other necessities to folks in Harriman Park. After the first few distributions, we realized we could do this bigger and more efficiently. I suggested setting up a produce stand to let everyone come and pick out what they want instead of deciding for them. We identified a vacant lot in Harriman Park near Keisha’s home to set up shop.

The first North B’ham Pop-Up Market in May was tiny compared with today.

We reached out to Jones Valley Teaching Farm, churches, volunteers, and other partners to help us source products. Keisha got the word out to the community and we held the first North B’ham Pop-Up FREE Market in May in a vacant lot in Harriman Park. In July we expanded to Mt. Hebron Baptist Church in Acipco-Finley on the west side of North Birmingham. Each market is basically an impromptu grocery store where the main attraction is fresh, local produce and socially distant fellowship.

“The Pop-Up Market has been a blessing to hundreds of people, including unemployed people, senior citizens, and big families,” Keisha said. “You save an extra $200 or more on fresh produce and personal items!”

This project grew organically from texts and phone calls between two people checking on each other during a truly scary time. There’s something beautiful about finding solutions in old-fashioned organizing and community caring. And at the end of the day, this is what “loving thy neighbor” looks like. I also believe this is the kind of community organizing that North Birmingham needs to build the power necessary to overcome decades of environmental racism and political corruption.

This is disruptive humanitarianism in action.

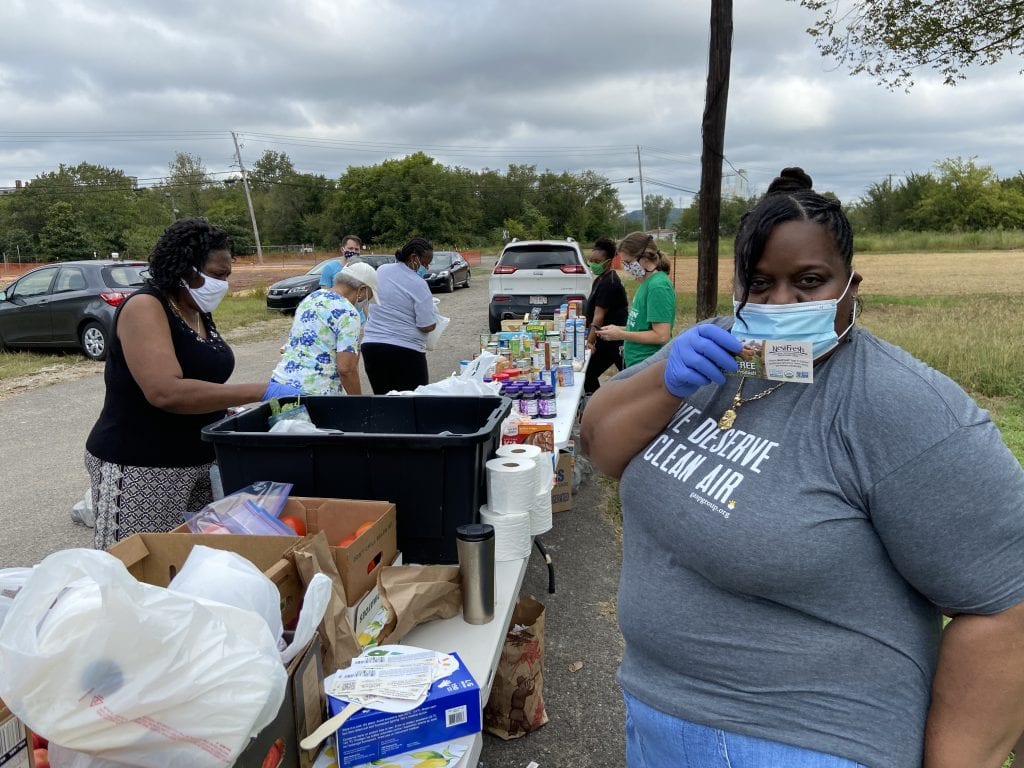

The Pop-Up Market on August 8 at Mt. Hebron Baptist Church in Acipco-Finley

Below are just a few of the highlights from the past five months.

- Jones Valley Teaching Farm has graciously provided more than 2,000 pounds of fresh, healthy produce.

- Churches and volunteers helped us collect more than 3,000 pounds of canned goods and other non-perishable food items.

- Volunteers from Bham Masks provided more than 1,200 homemade face masks.

- Dozens of volunteers have helped sort donations, load cars, set up tables, and staff the Market each week.

- Hundreds of families served and relationships strengthened.

We would like to keep this project going. If you’d like to support the North B’ham Pop-Up Market, please contact Michael Hansen. We need volunteers, financial support, and items for the market.

If you’re concerned with climate change and want to do something about it, I highly recommend you check out Arm in Arm. It’s not a project of GASP — but we do support it and hope you’ll join a local hub.

Keisha hands out coup ons for a free dozen Nest Fresh Eggs

Keisha Brown and volunteers set up for the North B’ham Pop-Up Market in Harriman Park.