Particulate matter (PM 2.5), otherwise known as soot, is a dangerous and deadly pollutant composed of metals, organic chemicals, and acidic substances. It is produced by power plants, vehicle tailpipes, other industrial sources, and wildfire smoke. Soot particles are so small—just two and a half microns (there are about 25,000 microns in one inch, for reference)—that once inhaled, they quickly get into the bloodstream. Soot is a significant health risk when it becomes thick enough to create black dust upon surfaces. Some residents in Birmingham live so close to industrial power plants that soot can easily collect on the sides of their homes, cars, and other surfaces. Soot threatens our health and environment, posing particular risks for children, seniors, and people with chronic illnesses.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has even studied the link between heavy exposure to soot and potential health risk. It has proven to be a public health epidemic proving that prolongment of particulate matter has links to a long list of severe medical conditions and diseases. These include asthma attacks, heart attacks, stroke, heart disease, COPD, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, low birth weight, greater risk of preterm birth, and higher infant mortality rates. In addition, recent studies have shown that even low levels of air pollution exposure, including soot, lead to increased risks of Covid-19 infection.

Particulate matter pollution is so lethal that a recent study found that soot causes anywhere from 85,000-200,000 deaths every year. Sadly, almost no American is spared the dangers of soot pollution. According to the American Lung Association’s (ALA) 2022 State of the Air Report, more than 63 million Americans experience unhealthy spikes in daily particle pollution, and more than 20 million Americans experience dangerous levels of this pollution on a year-round basis. Still, some individuals suffer more than others.

In particular, low-income communities and communities of color have disproportionally lived with and died from the negative health impacts soot causes. A recent study conducted by researchers at the EPA-funded Center for Air, Climate, and Energy Solutions found that the disparity in soot exposure between White Americans and Black, Latino, and Asian Americans was consistent across the country, in rural and urban settings, and at all income levels.

Birmingham is no stranger to soot pollution, either. For many years, the city’s history as a major epicenter for the iron and steel industries meant that the air and soil in North Birmingham—a largely lower-income, Black neighborhood situated next to industrial factories—were among the most polluted in the country. As recently as 2019, the ALA listed Birmingham as No. 14 on its list of American cities with the highest levels of year-round particulate air pollution. While the 2022 report found that the city’s year-round particle pollution levels were at their lowest yet, a sign of some progress, it still ranks 29 among the most polluted in the country. And, in a worrying sign, short-term particle pollution worsened in this year’s report compared to last year. Birmingham is the third worst city in the Southeast for this pollution.

While the health impacts of soot alone are scary, this pollution also poses severe environmental risks and speeds up climate change. That’s because soot is produced from burning fossil fuels, which are well-known to contribute to climate change. One study even found that a specific form of soot, called black carbon, is second only to carbon pollution in causing climate change.

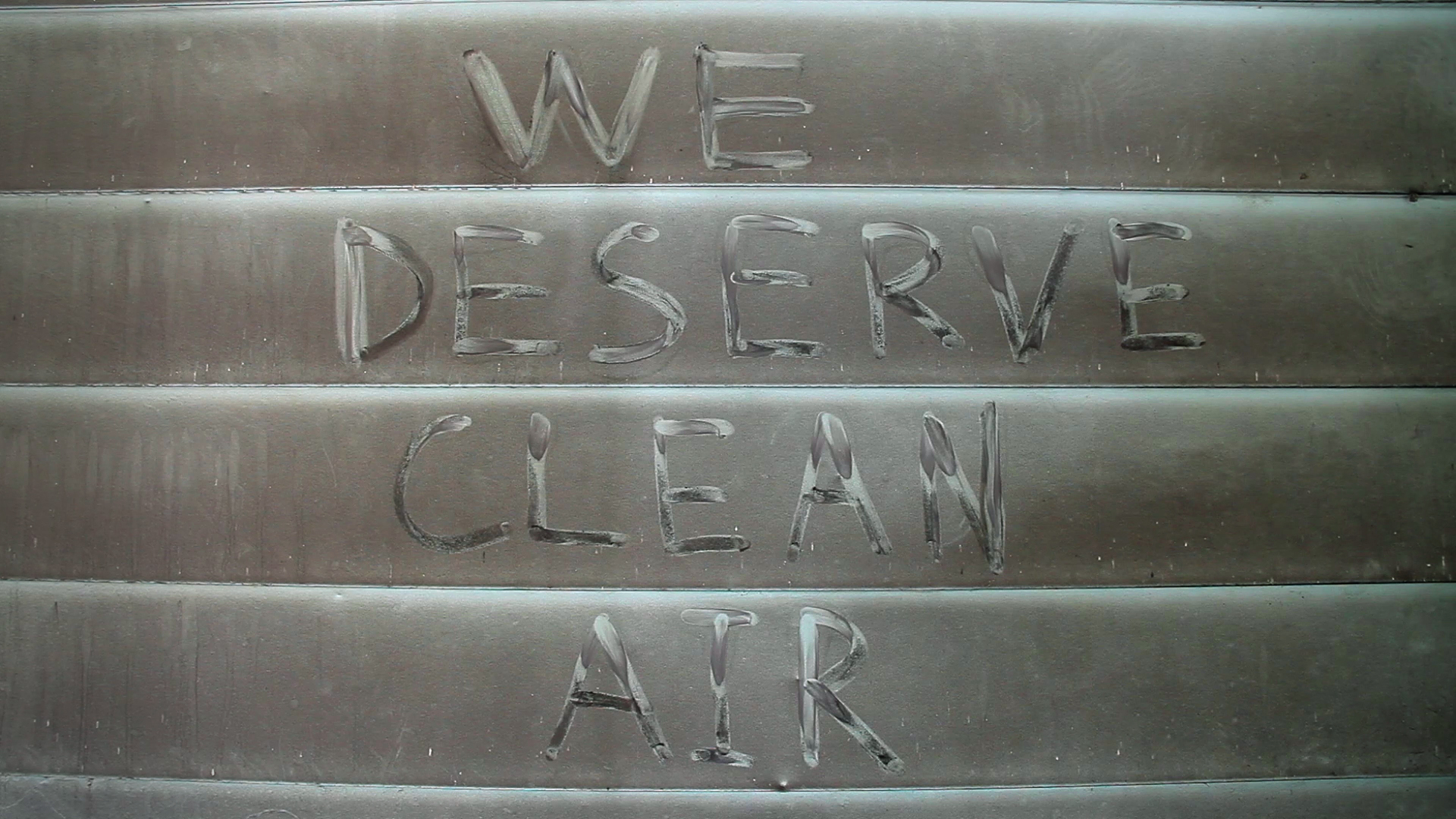

The EPA is currently considering updating its soot standards. Inaction by the previous administration means that they haven’t changed since 2012. Currently, the annual standard allows up to 12 micrograms per cubic meter of PM 2.5 in the air. The EPA’s soot standards must be lowered to no higher than eight micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3) for the annual standard and no higher than 25 μg/m3 for the 24-hour standard.

The science behind this is consistent and compelling. Even the EPA’s own Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) agrees the soot standard must be strengthened. Suppose the EPA lowers the allowable limits of soot pollution, as they should. In that case, they will significantly contribute to protecting public health, advancing environmental justice for all Americans, and saving thousands of lives.

Click HERE to sign our action alert for the EPA to strengthen its standards.