The Role of Health Departments in Promoting Environmental Justice

Background

If you’ve read anything else on this website, you probably already know about the environmental justice challenges facing Birmingham. Air pollution from industries and factories disproportionately affects communities of color and low-income neighborhoods, putting residents at a greater risk for diseases from asthma to cancer. Part of Gasp’s work includes trying to get the Jefferson County Department of Health (JCDH) to take action against this public health issue. This semester, I’ve been focused on research that will find examples of actions that other health departments have taken to promote environmental justice. Hopefully, after seeing what other departments are doing, the JCDH will have some ideas for promoting environmental justice here in Birmingham.

What I Found

I looked at three different cases to understand how health departments across the country have been addressing environmental justice. Two examples are from the southeast, so Birmingham can be compared to similar regions. The last example is from the west coast, so that Birmingham can be compared to the country at large.

North Carolina

Birmingham is not unlike other regions of the US in terms of its struggles with industrial pollution. In North Carolina, industrial food animal production is a critical pollution source. Contaminants from these facilities, which raise hogs and other animals, pollute nearby air and water. Rural, poor communities are the ones most affected. They live closer to the facilities and may lack the economic resources necessary to take care of their health.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins studied health departments in North Carolina and seven other states to see why health departments aren’t doing more to promote environmental justice. They identified what kind of help and support would allow health departments to be more effective: educational materials to hand out, more funding for the department, and more training for staff. This study gives a starting point for equipping health departments with the resources necessary to address environmental justice concerns.

Cover of the Environmental Justice chapter in Fulton County’s Comprehensive Plan for 2035

Fulton County, GA

Geographically speaking, this example was the closest to home! The Fulton County Board of Health got funding for an environmental planner in 2010, and one of the responsibilities of this position is to implement the board’s Environmental Justice Initiative (EJI). This is already impressive compared to Alabama; a search for “environmental justice” on the Jefferson County Health Department website brings up exactly zero results.

Under the EJI, the board added an environmental justice amendment to the Fulton County zoning regulations. The amendment defined “pollution point” and redefined “environmentally adverse use” and “environmentally stressed community.” It also provided separation distances to be maintained between environmentally adverse land uses and environmentally stressed communities. This is huge! We can’t fix environmental justice issues if we don’t acknowledge them first. Birmingham’s zoning ordinance does not have similar definitions; it discusses the importance of preventing “adverse environmental impacts” without defining what those impacts might be.

Another achievement of the Fulton County Board of Health’s EJI was getting an entire chapter dedicated to environmental justice in the county’s comprehensive plan for 2035. For Birmingham, environmental justice is mentioned in the first part of our comprehensive plan (“Understanding Birmingham Today”), but is never mentioned in the last chapter, titled “Stewardship and Implementation of the Plan.” In other words, our plan recognizes the issue of environmental justice, but it does not provide the steps we should take to address the problem.

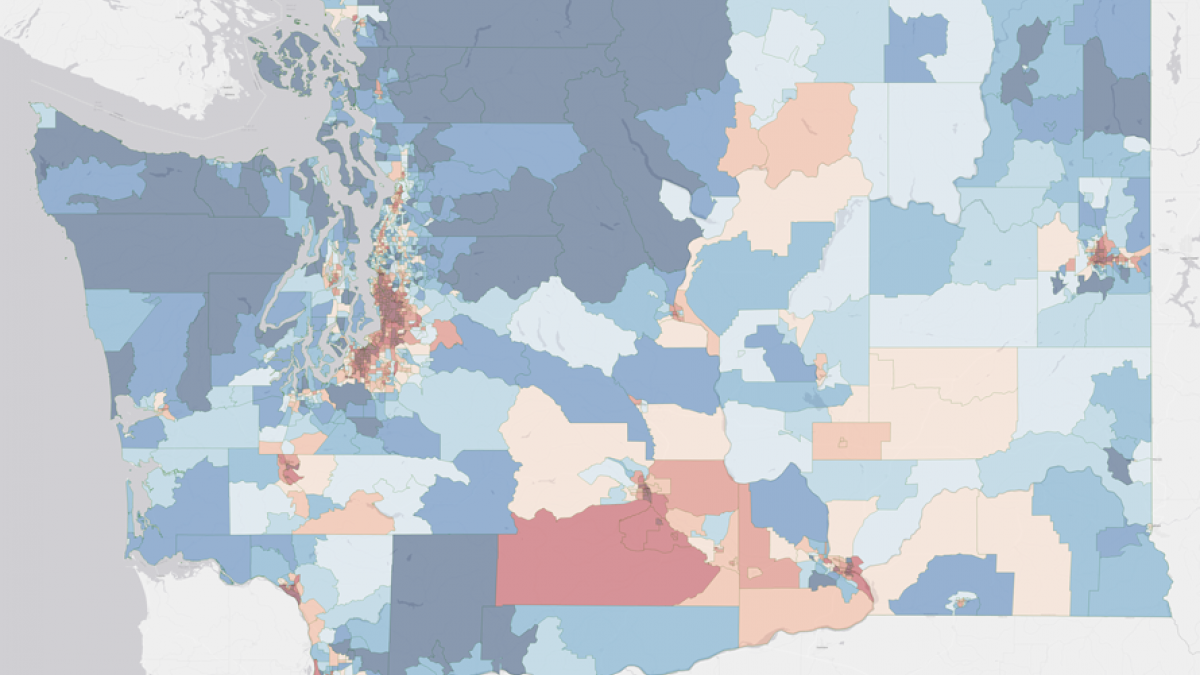

Interactive EJ Map from Washington

Collage of pictures from listening sessions in Washington

Washington State

My research with the southeastern cases confirmed the west coast’s status as a national leader in environmental affairs. In Washington, the state Department of Health was part of a collaboration with a plethora of partners, including the University of Washington and the Washington State Department of Ecology, to create an interactive environmental justice (EJ) map. The collaborative project started with eleven listening sessions — meetings throughout the state where residents were invited to be part of the process by voicing their environmental concerns. After that, a symposium was held so that researchers, government officials, and community members could decide what indicators to use for the EJ map. The final map was developed using indicators of pollution burden combined with population characteristics so that it ultimately shows where environmental risk is the most impactful (based on pollution exposure and the ability of that community to manage health risks).

There’s no tool like this in Alabama. Nationally, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched the EJScreen tool, but it provides a rough overview without being specific to communities within the state. For example, the EJScreen provides information about particulate matter and ozone, but it does not take Alabamians’ specific concerns into account. Washington’s EJ map reflects the concerns of individual residents. The result is a map that more accurately describes the state of environmental justice in Washington. Government officials can use the map to shape future policy decisions, so I’m excited to follow this example and see what happens in Washington in the future!

Reflections on Research

Here’s something that you and I and everyone else already knew: advocacy work is slow. So slow. Ridiculously, impossibly, tantalizingly slow — which is what makes it so admirable that this is the work to which people devote their entire lives. In researching the educational tools in North Carolina, the government plans in Fulton County, and the interactive map in Washington, I’ve done my own small part, but there’s still much more to be done. The research still needs to be presented to the Jefferson County Department of Health, and if they decide to take action, the ideas used across the country will need to be modified to suit Birmingham. The process is long, but that’s how you know that you’re working towards something worthwhile: a Birmingham that is cleaner and healthier for all its residents.

About the Author

Mariam Massoud

Volunteer

Mariam Massoud is a civil engineering major in the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Engineering. In 2018, Mariam was selected for the prestigious Fulbright US-UK Summer Institute Scholarship. She’s been an all-star volunteer with Gasp for the past year, assisting with research projects.