Despite the US Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education that laws mandating segregated schools are unconstitutional, today’s public schools are still profoundly segregated in many, or even most, areas of the country. More than 40% of Black and Latinx students nationwide still attend schools where at least 9 in 10 students are people of color. This is no longer because of laws that actively require school segregation, which is de jure segregation (segregation by right, or by law). It is because of neighborhood segregation caused by individual homeowner choices, real estate practices, banking discrimination, and municipal zoning board decisions. This is de facto segregation – segregation in fact

Our schools are segregated because our housing is segregated. Some cities and states bused students from one school to another, or even one district to another, to even out racial disparities. Busing was generally an unpopular remedy, however, and a 1974 Supreme Court case (Milliken v. Bradley) greatly limited its usefulness, finding that unless there were policies that pushed de jure segregation across district lines, busing students between districts to reduce school segregation was not allowed. More recently, in 2007, the Supreme Court again ruled against a school district attempting to actively desegregate in the face of de facto segregation, stating (perhaps in dewy-eyed optimism) in Chief Justice Roberts’s majority opinion that “[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Correcting past injustices, if those injustices came about “naturally” or at least without explicit governmental discrimination, is simply not a priority for Justice Roberts and today’s Supreme Court. And yet even if we agree with Justice Roberts that colorblindness is the answer to solving racism (we at GASP do not), the evidence that today’s persistent segregation is more than simply de facto happenstance is strong.

Author Richard Rothstein explains in his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America that governmental policies at all levels, from municipal to state to federal, were explicitly racialized and created the housing segregation we now live in. It makes no sense, Rothstein argues, to treat this federally sanctioned segregation as though it isn’t just a different kind of de jure segregation. Mob violence, aided and abetted by local police, enforced the “racial purity” of whites-only areas. State real estate commissions enforced ethics codes prohibiting realtors from integrating neighborhoods. The federal government granted tax exemptions to discriminatory nonprofits, placed public housing in segregated neighborhoods, and assisted in the redlining of entire cities—ensuring that only white people were able to get mortgages for houses in white neighborhoods. In Birmingham itself, Rothstein explains, the New Deal’s Public Works Administration built an all-Black public housing project in a neighborhood zoned for Black people. The legacies of these explicitly racist governmental policies still exist, in the form of the still-segregated housing and school systems.

So, what does this have to do with GASP?

At GASP, pursuing environmental justice is one of our core missions. Everybody has the right to breathe clean, healthy air and live in a truly livable community. We know that communities of color are more likely to be affected by pollution, including right here in Birmingham. Facilities that generate pollutants or hazardous waste are often located near areas with low property values already, and places where the residents may already be somewhat disenfranchised from the political process, so as to make any pushback from the site placement less likely. These factors, while race-neutral on their face, absolutely contribute to the disproportionate site placement of these facilities near Black neighborhoods.

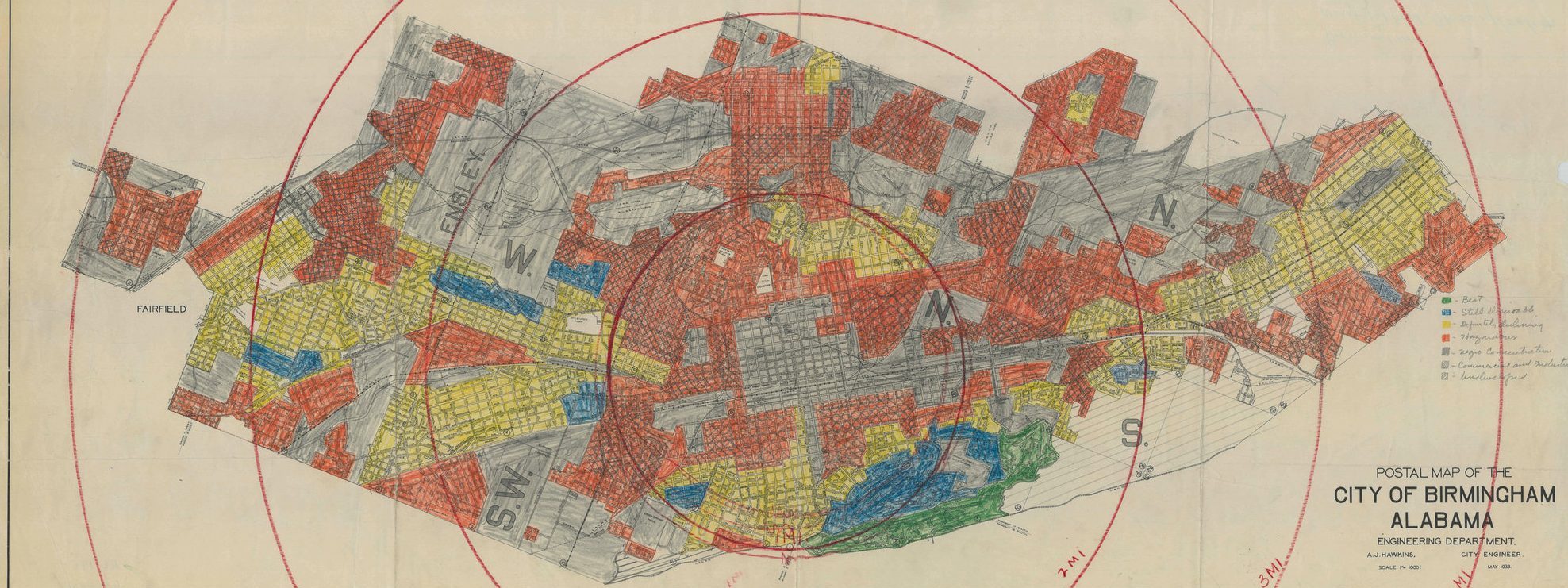

In 1926, Birmingham enacted a zoning ordinance that explicitly divided the city up into some areas for white people, and some for African-Americans. This zoning map was enforced even into the 1950s after racial zoning was officially outlawed, and the areas drawn as Black communities in the zoning map were reinforced by federally endorsed redlining starting in the 1930s. Today, industrial sites sit closest to the Black neighborhoods from the zoning map, leaving the residents of those neighborhoods at higher risk of pollutant-related health problems de facto because of racist de jure segregation from a century ago.

We need to recognize that these modern problems often have substantial historical roots in harmful and discriminatory official government policies from the past. Governmental action helped to ensure that the places we live in, the schools we go to, the health problems we have, and even the quality of the air we breathe are likely to depend in part on what race we are. It makes no sense that our ability to correct these historical wrongs, the ones that reverberate still, depends upon whether segregationist institutions were sufficiently explicit with their discriminatory policies.

In spite of the tremendous civil rights history of the city, Birmingham remains one of the most segregated cities in the United States. Our history of segregation has helped to enable environmental catastrophes like that in North Birmingham, where coal-fired coke plants and other heavy industrial facilities have pumped toxic chemicals into the air, water, and soil of a historically Black segregated community. If we truly want to get serious about building a more equitable Birmingham, we shouldn’t, and can’t, simply depend on things like “market forces” to right these wrongs. Our best hope is to tackle these problems actively, together, with an honest look at the historical choices that have led us to where we are today. Environmental justice is housing justice and educational justice; while some of these issues may have their own individual solutions, the underlying causes are all linked and must be grappled with holistically. It is beyond time to get started.

Other Sources:

https://theconversation.com/what-school-segregation-looks-like-in-the-us-today-in-4-charts-120061

https://kappanonline.org/myth-de-facto-segregation-rothstein-school-districts/

https://www.greenamerica.org/climate-justice-all/people-color-are-front-lines-climate-crisis

https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/arz40&div=44&id=&page=

https://gaspgroup.org/environmental-justice/

https://racism.org/index.php/en/articles/basic-needs/propertyland/2317-the-legacy-of-racial