“When I came down there to help…I didn’t know that I was going to form an organization…that was going to help the Birmingham area of Fairmont, Harriman Park, Collegeville.” Charlie Powell, director of People Against Neighborhood Industrial Pollution, also known as PANIC, reflects on the creation of the organization. PANIC was created in 2012 when Lois Gibbs, the “mother of the Superfund” visited Birmingham during that time to speak with communities facing industrial contamination.

Gibbs is the 1990 Goldman Environmental Prize winner for the United States after organizing her community against the toxic chemical waste at Love Canal, New York in 1978. During her visit she encouraged the three north Birmingham neighborhoods to come together and form a base organization that could fight against industrial pollution. At the end of the meeting Gibbs asked the crowd of almost 100 people, “Who in this room will lead the cause to form a citizen-based organization?” And Charlie Powell stood up.

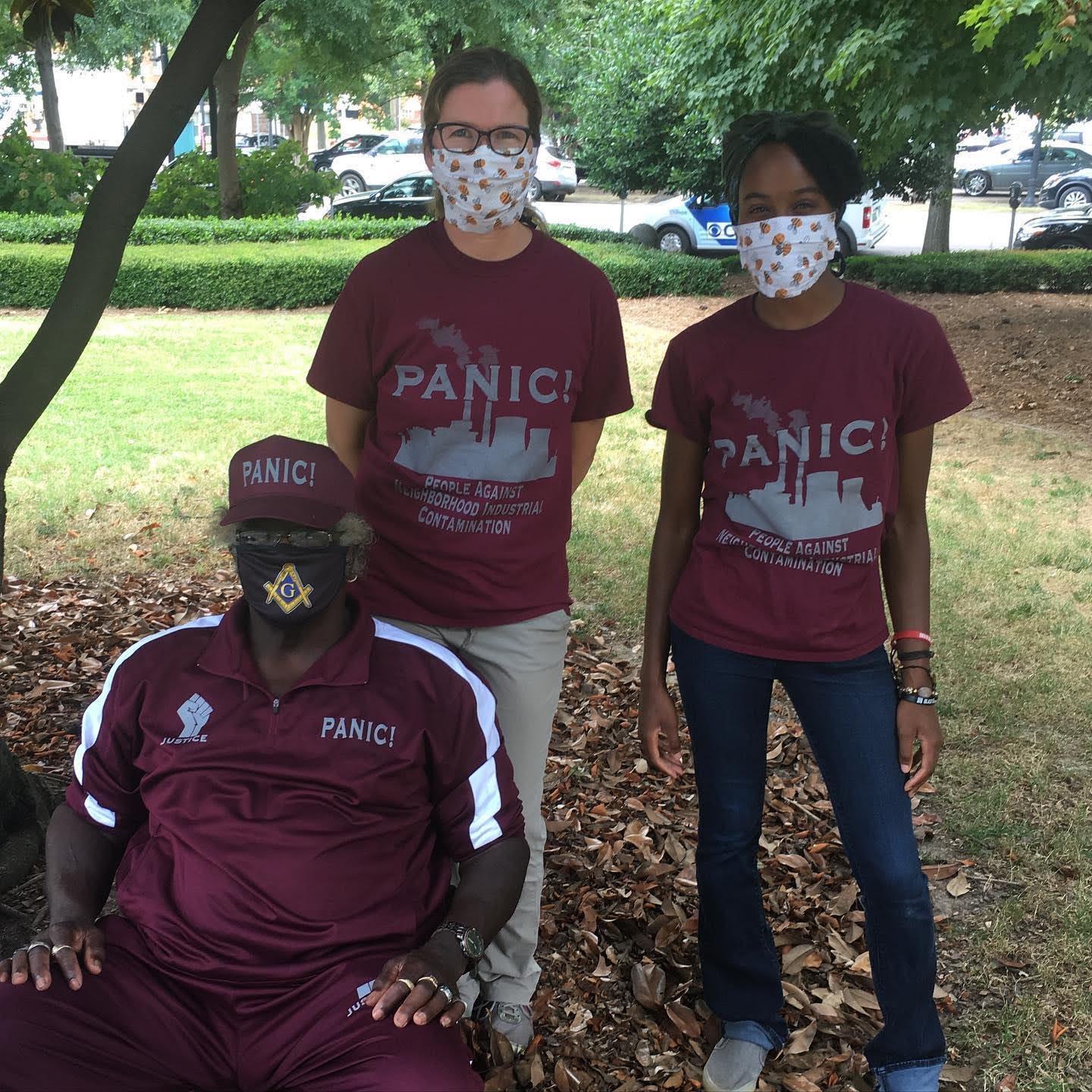

- Charlie Powell, Kirsten Bryant, and Nina Morgan at an event for PANIC in 2020.

- Charlie Powell founder of the community advocacy group People Against Neighborhood Industrial Contamination leading monthly PANIC meeting – Charity Rachelle for ProPublica

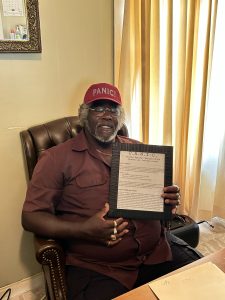

- Charlie Powell holding PANIC’s Mission

This is not the future he had envisioned for himself after growing up in the nearby neighborhood of Riggins during the 1960s. Growing up in a family of 16 children, Powell had plenty of playmates and plenty of snacks on their small farm. He and his siblings would travel around their close-knit community picking up apples and tomatoes from gardens and eating them immediately. “Those are the things…we found out that we shouldn’t have been doing later on.” Over the years several of the north Birmingham communities, including Riggins, Vice Hill, and Lewisburg became smaller as people began to leave the area. Eventually they were all added into the Fairmont neighborhood, which has a population of 2,568 residents.

Powell first moved to Fairmont in 1972 after graduating and getting married. After 42 years, he moved to Center Point, and then decided to move back “to try to help my people.” During this time the EPA had designated parts of north Birmingham as the 35th Avenue Superfund site. Powell had mixed emotions as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) came to his home and declared it an emergency cleanup. On one hand, the minimum score to be considered contamination was 25, and his score was 50. On the other hand, the EPA spent $75,000 cleaning up his property when it was only valued at $50,000. The Riggins school, three miles from his home, was contaminated so badly that it had to shut down. Powell didn’t understand the EPA’s explanation of how the contamination had spread to some areas and not others because of the wind. It didn’t help that their estimation for the houses to be contaminated was 10,000 to 1; there weren’t 10,000 people in all the neighborhoods combined!

Powell doesn’t understand why the EPA has not helped the community residents move to a healthier area for those who are interested in doing so. PANIC’s stance on a solution for the industrial pollution is to offer citizens a buyout of their property, relocation options, or compensation for the residents not willing to leave. Powell has several properties in the area, and he has seen taxes rise as property values fall. This is the difficulty community members face when it comes to staying in a home their family has possibly lived in for generations. Referring to redlining, Powell says, “Black folks had a limited amount of places where they could live. And they were always around steel mills, coke and chemical plants.” These industries offered jobs where employees could walk to work. There was also a commissary nearby where employees could buy a car, clothes, or groceries. “If you say the plant was good to them, maybe the plant was good to them because they knew the plant was killing them all the time.”

- Child playing in Birmingham, 1972 LeRoy Woodson/EPA/National Archives

- Smog in north Birmingham, 1972. LeRoy Woodson/EPA/National Archive

- Walter Coke Industiral Plant Overhead view 2021

Before the creation of the Clean Air Act in 1970, “It used to just rain stuff on us. You know, it would be all on our houses.” Powell’s family would hang their clean clothes on a drying line outside and have to bring them back in before too long because soot would make them dirty again. “I believe up until this day, if any of our fathers knew they (were) bringing us into an environment like this here, they never would (have).” Powell will never understand how two coke plants (ABC Coke and Bluestone Coke) were able to be built three miles from each other. “I think if anybody got a job they should make a fair profit. But not a fair profit in the cost of human lives.” Now that Bluestone Coke is no longer operating after litigation that GASP pursued, Powell states there is another problem – 400 acres of toxic pollution.

Charlie Powell with Massachusetts Institute of Technology students during 2023 Civil Rights Immersive Tour

“I’ve always said what they should do is make that industrial park and just move our peoples out of there.” Powell is interested in selling some of his own properties, one of which is the current PANIC office. From 2012-2019, he spent his own money on PANIC and is glad to see how far it’s come. He says everyone is welcome to come and visit him anytime at 110 74th St South. This work brings him immense joy because he is fighting for the lives of people he loves in these communities. At the time of this interview, Powell was preparing for the funerals of his niece and nephew, who both died from diabetes and cancer. In 2023 he mourned the loss of three other nephews, who all died from cancer. And his wife, who grew up in Collegeville and gave PANIC its name, now has stage 4 cancer. “So I am doing this for them…I think if I can get this resolved, I will be a happy man.”